By Ronald Rychlak, Ph.D.

(The American Conservative, February 10, 2003)

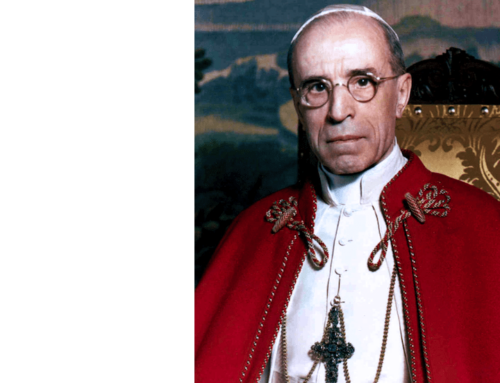

In 1999, John Cornwell fired the first round in a new assault on the papacy, the Catholic Church, and ultimately Christianity itself with his book, Hitler’s Pope: The Secret History of Pius XII. Cornwell’s thesis was that Pope Pius XII, who led the Catholic Church from 1939 until his death in 1958, was so concerned about centralizing authority in a strong papacy that he turned a blind eye toward the growth of the Nazis. Most readers took this book strictly as an historical charge against a long-deceased Pope, but those who followed it all the way to the end saw that much of the author’s hostility was actually directed at the current pontiff, Pope John Paul II.

Quick on his heels of Hitler’s Pope came a string of books (at least seven) that leveled new charges of anti-Semitism and blamed Christianity for the Holocaust. The culmination comes with the book by Daniel Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair. In it, Goldhagen claims that the Catholic Church provided the Nazis with a “motive for murder” and should be held to a moral reckoning for its sinful behavior. He argues that the authors of the New Testament (he calls it “the Christian Bible”) inserted anti-Semitic passages into the text decades after the crucifixion in order to serve their own political needs. As such, Goldhagen’s book is not simply an attack on the papacy or the Catholic Church, but on Christianity itself, especially the New Testament, which Goldhagen says is “fictitious” and “not a reliable rendition of facts and events, but legend.”

Goldhagen’s focus is on those passages of the New Testament that long have been recognized as containing language that can be misunderstood. Of particular concern is Matthew 27:24-25, where Jesus is handed over to the Roman authorities, ultimately to face crucifixion. Pontius Pilate offered to free one of the “criminals,” and the crowd called for Barabbas. As Matthew reports:

So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.”

And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!”

Goldhagen argues that Matthew here falsely attributes blame for the crucifixion to all Jews for all times, that this instilled a hatred of Jews into the European psyche, and that Hitler merely had to exploit this pre-existing attitude to his own perverted ends.

The remedy that Goldhagen proposes includes having Christians agree that Christ is not the only way to salvation and having them (with help from non-Christians) re-write the Gospels to purge offensive, anti-Semitic passages. He goes on to demand that the Catholic Church make reparations to Jews. He says that money reparations are deserved; political reparations are useful; but above all he stresses the need for the Church to admit its moral failings. He asks for apologies, the erection of suitable monuments, an end to the Church’s diplomatic relations with other nations, support for Israel, and repudiation of any claim that Christianity has supplanted Judaism. Instead, the Church must embrace religious pluralism, acknowledging that salvation is not limited to the Catholic Church or to Christianity. (Along the way, he also tells us that white southerners should make restitution to African-Americans for slavery and segregation.)

Let us first be clear that the Catholic Church does not read Matthew the way that Goldhagen suggests. At the Second Vatican Council, the Church made clear that guilt for Jesus’ death isnot attributable to all the Jews of that time or to any Jews of later times. The Catholic Church has always understood that Jesus was born into a Jewish family. His mother was Jewish. His early followers were Jewish, and the people who first heard him preach were Jewish. As Pope Pius XI said in 1938:

Mark well that in the Catholic Mass, Abraham is our Patriarch and forefather. Anti-Semitism is incompatible with the lofty thought which that fact expresses. It is a movement with which we Christians can have nothing to do. No, no, I say to you it is impossible for a Christian to take part in anti-Semitism. It is inadmissible. Through Christ and in Christ we are the spiritual progeny of Abraham. Spiritually, we are all Semites.

Goldhagen actually tries to twist this proclamation to show that Pius XI was an anti-Semite, but he fails. In January 1939, the National Jewish Monthly reported that “the only bright spot in Italy has been the Vatican, where fine humanitarian statements by the Pope have been issuing regularly.”

Certainly no one would suggest that Christians and Jews have gotten along well at all times throughout history. Prior to 1870, when Popes had real temporal power, Jews were sometimes treated with religious and political contempt. Many Catholic officials of this period were fearful that Jews would lead Christians away from Christ, or worse. They found reason for their fear in Old Testament passages such as Joshua 6:21 (Jews “observed the ban by putting to the sword all living creatures in the city: men and women, young and old, as well as oxen, sheep and asses.”), Deuteronomy 20:17 (“You [Jews] must doom them all….”), and Deuteronomy 7:1-5:

When the LORD, your God, brings you [Jews] into the land which you are to enter and occupy… and you defeat them, you shall doom them. Make no covenant with them and show them no mercy…..Tear down their altars, smash their sacred pillars, chop down their sacred poles, and destroy their idols by fire. For you are a people sacred to the LORD, your God; he has chosen you from all the nations on the face of the earth to be a people peculiarly his own.

In 1564, Pope Pius IV announced that the Talmud could be distributed only on the condition that the portions offensive to Christians were erased. Earlier Popes had, at times, banned it altogether.

These measures are not reflective of happy periods in the history of Christian-Jewish relations, but almost all papal critics acknowledge that throughout even the worst periods Popes regularly condemned violence directed against Jews and offered protection when they could. This Catholic “anti-Judaism” was a matter of religion, not race. In fact, the more common charges arising out of this history related to efforts directed towards encouraging Jews to convert—to become Catholics.

By contrast, Nazi racial anti-Semitism did not encourage Jews to “join the party.” This “scientific” position drew support from biological arguments and the absence of religion. Nazis showed films equating Jews, handicapped persons, and other “undesirables” with vermin that needed to be exterminated. This was in direct contradiction to everything that the Catholic Church had always taught about the fundamental dignity of all human life.

Does this mean that is was impossible for Hitler to lay claim to Christian teachings as he advanced his evil agenda? Of course not. In Mein Kampf, Hitler went to great length about misusing religious imagery to inspire and inflame the masses. Hitler also played to a populist mentality, a racist mentality, a socialist mentality, a chauvinistic mentality, a nurturing/mothering mentality, a scientific mentality, and just about any other mentality that he could think of. Are they all to be condemned because they were capable of being manipulated by Hitler (who also planned to eliminate largely-Catholic Poland)? The answer is equally clear: of course not.

In order to understand the dynamics of the time, one only need examine Nazi arguments from the 1930s and 40s. Hitler regularly complained about Christian interference with his plan (saying one time that the Pope was blackmailing him). Nazis propaganda often showed Jews invoking Christian imagery or hiding behind church symbols for protection. Several such drawings are reproduced in Konrad Löw’s new book, Die Schuld: Christen und Juden im Urteil der Nationalsozialisten und der Gegenwart, which was just published in Germany.

Goldhagen’s book is not based on original historical research. He just culled the worst accusations from authors like Gary Wills, Susan Zuccotti, John Cornwell, and others without giving any consideration to the serious flaws that have been noted in their books. Goldhagen takes many of his larger themes from Constantine’s Sword by James Carroll, an ex-priest, whom Goldhagen calls “a devout Catholic.” Carroll hardly sounded that way in his memoirs, when he scoffed at his excommunication from the Catholic Church. More troubling, however, is the way Goldhagen’s selectively used secondary sources to manufacture arguments.

Goldhagen’s main source for his charges about the Vatican allegedly helping Nazi War criminals escape justice is Michael Phayer’s book, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965. Phayer, in turn, draws mainly from the conspiracy-monger John Loftus and his discredited book, Unholy Trinity: The Vatican, the Nazis and the Swiss Banks. More recently, Loftus has accused the Bush family of establishing a fortune by laundering money derived from the Nazis.

Similarly, Goldhagen relies heavily and uncritically on Susan Zuccotti’s book, Under His Very Windows, for his analysis of that period of the war when the Germans occupied Rome and northern Italy (1943-44). One of Zuccotti’s chief sources, in turn, is the notorious Robert Katz–who was successfully sued by relatives of Pope Pius XII and publicly condemned by Italy’s highest Court for defaming the wartime Pope.

Goldhagen blindly accepts John Cornwell’s mis-translation of a letter written in 1919 by Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII, when he was papal nuncio in Munich. That year, Bolshevik revolutionaries temporarily took power in Bavaria and began operating what might best be described as a rogue government. Pacelli sent his assistant, Monsignor Lorenzo Schioppa, to meet with the Bolshevik leader, Eugen Levine, to determine whether representatives in Munich would be accorded diplomatic status. Levine responded by saying that he would recognize the extra-territoriality of the foreign legations “if, and as long as the representatives of these Powers…do nothing against the [Bolshevik government].” He made it clear that he “had no need” of Vatican representatives.

Pacelli wrote a six page letter back to Rome reporting on this meeting. The key passage, as translated by Cornwell (and accepted uncritically by Goldhagen), described the scene at the palace as follows:

… in the midst of all this, a gang of young women, of dubious appearance, Jews like all the rest of them, hanging around in all the offices with lecherous demeanor and suggestive smiles. The boss of this female rabble was Levien’s [sic] mistress, a young Russian woman, a Jew and a divorcée, who was in charge. And it was to her that the nunciature was obliged to pay homage in order to proceed.

This Levien [sic] is a young man, of about thirty or thirty-five, also Russian and a Jew. Pale, dirty, with drugged eyes, hoarse voice, vulgar, repulsive, with a face that is both intelligent and sly.

Goldhagen suggests that these 106 words, based on Schioppa’s report, prove that Pacelli was an anti-Semite. In truth, however, this translation is grossly distorted.

The phrase “Jews like all the rest of them” is a distorted, inaccurate translation of the Italian phrase i primi. The literal translation would be “the first ones” or “the ones just mentioned.” Similarly, the Italian word schiera should be translated as “group” instead of “gang.” Additionally, the Italian gruppo femminile should be translated as “female group,” not “female rabble.” The Italian occhi scialbi should be translated as “pale eyes” not “drugged eyes.”

When the entire letter is read with an accurate translation, it loses its anti-Semitic tone, which was introduced only by the bogus translation upon which Goldhagen relied. Moreover, that is not the only translation problem with A Moral Reckoning. Jody Bottum, writing in The Weekly Standard, says: “there isn’t a Latin phrase in the book that doesn’t have an odd translation.”

When Goldhagen is unable to find outrageous charges that others have already advanced, he seems willing to manufacture false evidence to support his case. For instance, the photograph on the cover of A Moral Reckoning shows a Nazi sign (“Jews not welcome here”) near what Goldhagen calls a “Catholic shrine.” Supposedly this implies some kinship between the Church and the Nazis. According to German reviewers, however, this is not a single photo but a collage that brings the two images together.

A German court even ordered Goldhagen’s book to be pulled from the shelves due to a caption beneath a photo showing a Catholic prelate surrounded by Nazis. The caption said: “Cardinal Michael Faulhaber marches between rows of SA men at a Nazi rally in Munich.” In fact, the photo shows papal nuncio Cesare Orsenigo, not Bavarian bishop Faulhaber. The city is Berlin not Munich, and it isn’t a Nazi rally but a May Day parade. Faulhaber was a staunch foe of the Nazis, and his diocese reports that he never attended a Nazi rally. Orsenigo was nuncio and ex-officio dean of the diplomatic corps, so he was expected to attend this parade which celebrated workers, not Nazis.

Another of Goldhagen’s most blatant errors relates to the Franciscan friar Miroslav Filipovic-Majstorovic, also known as “Brother Satan.” Goldhagen ends his discussion of Croatia by writing: “Forty thousand…perished under the unusually cruel reign of ‘Brother Satan,’…. Pius XII neither reproached nor punished him…. during or after the war.” Actually, “Brother Satan” was tried, defrocked, and expelled from the Franciscan order before the war ended. In fact, his expulsion occurred in April 1943, before he ran the extermination camp. For Pius XII to have punished him “after the war” would have been difficult indeed, since he was executed by the Communists in 1945.

Goldhagen argues that the Vatican “endorsed” Italy’s anti-Semitic laws. Actually, Mussolini’s “Aryan Manifesto” was issued on July 14, 1938. On July 28, 1938, Pius XI made a public speech in which he said: “The entire human race is but a single and universal race of men. There is no room for special races. We may therefore ask ourselves why Italy should have felt a disgraceful need to imitate Germany.” This was reprinted in full on the front page of the Vatican newspaper on July 30, under a four-column headline. Other articles condemning anti-Semitism (and I may have missed some) appeared on July 17, July 21, July 23, July 30, August 13, August 22-23, October 11-18, October 20, October 23, October 24, October 26, October 27, November 3, November 14-15, November 16, November 17, November 19, November 20, November 21, November 23, November 24, November 26, December 25, and January 19, 1939.

One of the most amazing parts of A Moral Reckoning is where Goldhagen attempts to construe the US Bishops’ 1942 statement as a slap at Pius XII. At their annual meeting in November 1942, the U.S. Bishops released a statement on the plight of the Jews in Europe. It said, in part:

We feel a deep sense of revulsion against the cruel indignities heaped upon Jews in conquered countries and upon defenseless peoples not of our faith…. Deeply moved by the arrest and maltreatment of the Jews, we cannot stifle the cry of conscience. In the name of humanity and Christian principles, our voice is raised.

Goldhagen tries to turn this statement into a slap at the Pope and an “all but explicit rebuke of the Vatican.” Actually, the American bishops repeatedly invoked Pius XII’s name and teachings with favor (“We recall the words of Pope Pius XII;” “We urge the serious study of peace plans of Pope Pius XII;” “In response to the many appeals of our Holy Father”). Moreover, in a letter written at this very time, Pius expressed thanks for the “constant and understanding collaboration” of the American bishops and archbishops. They replied with a letter pledging “anew to the Holy Father our best efforts in the fulfillment of his mission of apostolic charity to war victims.” They also offered a prayer for the Pope’s charitable collaborators. The very idea that the bishops were trying to insult the Holy Father is preposterous.

Actually, the Catholic Church itself is a particularly unwise target for Goldhagen to have chosen. It is easy enough to find sloppy interpretations of the Bible or hate-mongers bending it for their own purposes, but the Catholic Church has a hierarchy and official teachings on these matters. Goldhagen avoids that reality. In fact, he provides no evidence for his principal assertion that the guilt of all Jews for the crucifixion was a “central Catholic doctrine” and teaching it was “official Catholic Church doctrine.” In point of fact, the Catechism of the Council of Trent, the authoritative statement of Catholic doctrine during the Nazi period, says something quite different: “All sinners were the authors of Christ’s Passion.”

Goldhagen likewise presents no evidence that Germans who were brought up with a traditional Catholic education were more likely to support or join the Nazi party than were other Germans. In fact, Hitler tended to fare worse at the polls in Catholic areas than he did in non-Catholic parts of Germany. None of the Nazi leaders left evidence suggesting that they participated in the killing because they thought of their victims as deserving death due to the Gospels. Perhaps most shamefully, Goldhagen disparages all the good that Pope John Paul has done to advance relations between Catholics and Jews over the past quarter of a century.

Clarifying the events surrounding the crucifixion and working toward a better understanding of the truth are legitimate pursuits for Bible scholars. In fact, there is a vast body of writing that analyzes these issues in detail. Unfortunately, Goldhagen appears to be unfamiliar with most of it. He says that Catholic teaching has always “revised” its essential beliefs. That is certainly not true, and it reflects a fundamental ignorance of the topic on which he purports to write. The documents of Vatican II maintain a clear and unqualified connection with the original Deposit of Faith. The Catholic Church, according to its own teaching, does not have the authority to rewrite scripture or deny the ultimate divinity of Christ. (Can you imagine the divisions that would take place within Christianity if it tried to do so?)

Those who are interested in learning more about Catholic teaching regarding relations with Jews (which should include every reviewer who treated Goldhagen’s book with any degree of respect) are advised to read Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican Council’s renewal of the Church’s condemnation of anti-Semitism. That is a far better way to approach this subject than by reading A Moral Reckoning, which in the end is nothing more than a sloppily written polemic rant.

Professor Ronald J. Rychlak is the author of Hitler, the War, and the Pope (Our Sunday Visitor, 2000).

Copyright © 1997-2011 by Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights.

*Material from this website may be reprinted and disseminated with accompanying attribution.